My love for wild winemaking probably comes from my grandfather, who made a coconut drink called "tuba." I used to watch him collect the sap from coconut trees and turn it into an alcoholic drink, and it always amazed me. Now, I do something similar with wild berries and fruits I pick. Whether it's blackberries or elderberries, making wine from what I forage feels like a fun way to keep that family tradition alive.

Autumn is the best time to make them, the abundance of juicy, sweet blackberries around this time, with their rich, fruity sweetness, makes for a wonderfully smooth and aromatic wine!

Picking wild berries after the heavy rain is my favourite time—they are fresh and plump!

These dark, plump beauties grow wild along hedgerows, meadows, and woodland edges.

They are at their peak, with deep purple-black, soft to the touch, and easily come off the bramble with a gentle tug.

I filled my basket, and it’s time to turn them into something special—blackberry wine!

After trying so many types of berries, I decided to stick to blackberries this year. They are easier to make, and I don’t need to cook them like elderberries to remove cyanide, giving me more peace of mind. Blackberries have been giving me beautiful-tasting wine!

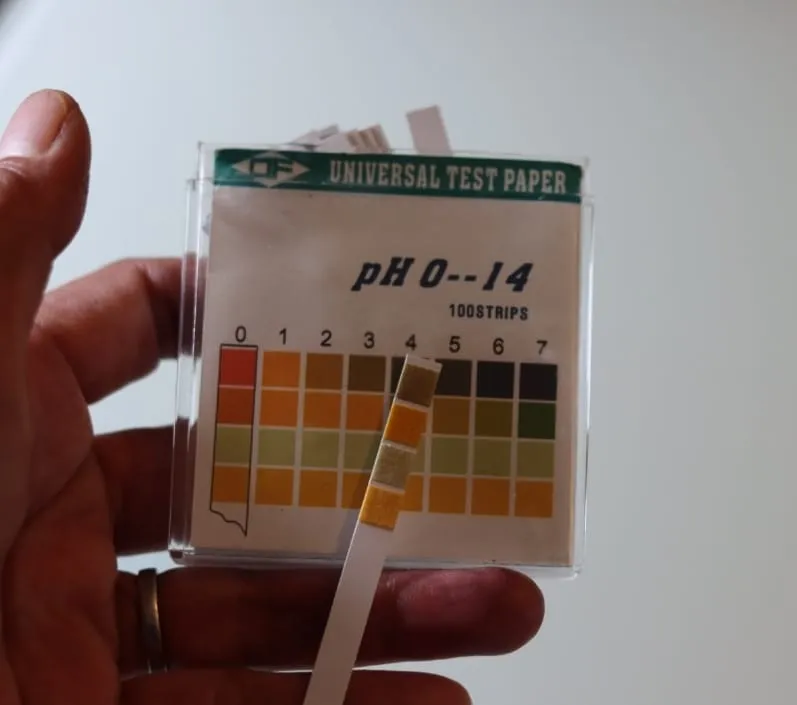

It's just a quick test strip from my finished wine from last year.

(I recommend a digital ph tester, though for accuracy)

I also didn’t need to add acids. It seems blackberries have balanced acidity and tannins, which likely helped the yeast survive for a while, producing a good amount of alcohol. Balanced acidity is crucial in winemaking—it prevents bad bacteria from growing. Acid levels should be between 3.2 and 3.6. If they get too high, bad bacteria can grow; if they get too low, the wine will become overly acidic or sour. A good balance helps the wine last longer and avoid spoilage.

With elderberries around here, I didn’t have to do much, and they had good yeast!

Here's how I do it.

3–4 pounds (1.5–2 kg) of wild blackberries (unwashed, to retain the wild yeast)

2 ½ pounds (1.1 kg) of granulated sugar

1 gallon (4 liters) of water

1 lemon juice (if the fruit acidity is low)

A fermentation vessel (bucket or demijohn) with an airlock

(This recipe will potentially reach 17-20% ABV). The yeast will naturally die when the alcohol reaches 20%, and the presence of alcohol will deter the growth of harmful bacteria, including mold.)

I don’t rinse my blackberries—their skin is full of yeast, and washing them, especially with chlorinated water, could kill them. Yeast is the main worker in making this beautiful wild wine.

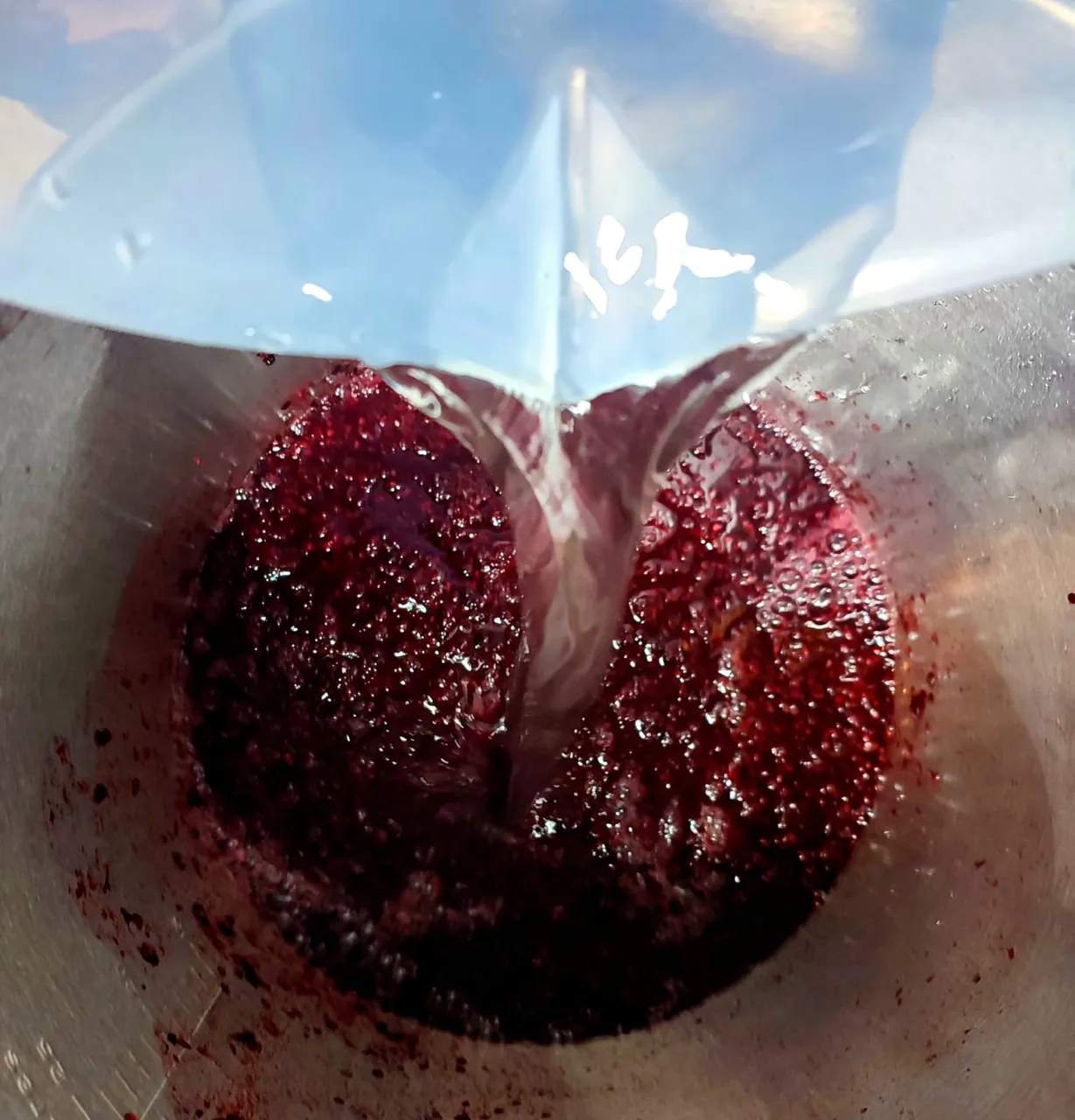

I mash them to release their juices. This stage is comparable to the traditional method of stomping grapes. This is called must.

Then, I transferred the must into the fermenting vessel.

I added water.

followed by sugar. I find that not melting the sugar and not stirring it for 24 hours gives the wild yeast a natural start. Lots of sugar can overwhelm and make yeast lazy. As the sugar naturally dissolves, the yeast will consume it gradually, turning it into alcohol.

Then, I put in an airlock, which prevents contamination from outside air but lets out the gas that the yeast produces during the fermentation.

This is how it looks after three days in the fermentation vessel. Some bubbles on the top, the yeasts have been producing gas as they convert the sugar to alcohol.

Usually, the first fermentation lasts 5–7 days. After that, the fruit pulp is strained, and the liquid (now called young wine) is transferred to a fermentation vessel with an airlock or demijohn, ready for the second fermentation.

The second fermentation, which lasts 2–3 weeks, continues to work on the sugar, and the wine will start to clear. At this stage, I rack or siphon it into another container to remove the sediment (this is optional)

However, a couple of years ago, I neglected my blackberry wine and didn’t strain or rack it. I left it in the fermenting vessel for a year after my initial mix, and I was amazed to have created the most beautiful wine! I was surprised.

So, I decided to recreate it by just leaving my wine alone. Less fuss, straight into my fermenting vessel!

I stirred or shook it daily at the start until the pulp sank to the bottom, avoiding mold formation, and then left it alone until it turned into a beautiful wine. The pulp added more flavour to the wine. The sediment naturally sinks to the bottom, leaving clear wine on top.

There’s just a little bit of straining before bottling—that’s all. If I need to clear it, I mix an egg white with a little water or wine (pasteurized or gently heated in a double boiler until hot to the touch). Adding one egg white per gallon is enough. After a few days, all the sediment sinks, leaving a clear wine ready for bottling. As it ages, the flavor deepens and mellows—longer aging results in a smoother wine.

I find my simple approach to homemade blackberry winemaking so rewarding, as I just let the wine develop its flavor naturally over time.

The wine becomes even more delicious with each passing month, and with less handling, there are fewer contaminations with harmful bacteria.

The rich, fruity sweetness of blackberries makes for a wonderfully smooth and aromatic wine that is perfect for cozy autumn nights.

If you haven’t tried making homemade wine yet, give it a try—you’ll be surprised!

Happy foraging, and cheers to a fruitful harvest!

Mariah 💜😊